The brilliant, if eccentric and self-congratulatory

Vladimir Vapnik has been trumpeting

a major shift in the scientific method, and perhaps our epistemological stance, over the past few years. Whether or not Vapnik gets his revolution, at the very I least I'll wager you will see

"transductive inference" gain increasing attention as his ideas trickle out from statistical learning theory to other intellectual fields. So what's it all about?

The goal of science (it can be argued) is the accurate prediction of future or novel events. Since the days of

Aristotle, and especially since

Bacon, the essential means of scientific inference is

induction. Bearing

Hume's warnings in mind, we generally follow this familiar process:

- Make a number of observations

- Induce a general law (or mathematical function) that we think is generating the phenomenon.

- Use the law to make predictions about future phenomena.

To simplify the discussion, let's restrict ourselves to a problem of

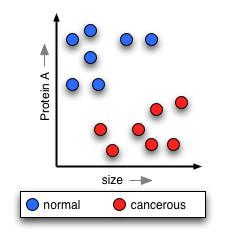

classification. You are encountering a steady stream of objects -- say, liver cells. First you get a batch (the "training set") which are labelled in two groups, say "normal" vs "cancerous". Your goal (especially in applied science) is simply to devise a rule by which you can

accurately classify future cells (the "test set") as normal or cancerous.

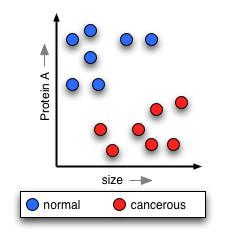

To make your classification, you measure

various characteristics of the liver cells; for example, size, color, mitotic activity, expression level of various proteins, etc. For simplicity, let's suppose you measure just two characteristics, size and the level of "protein A". You could draw a graph plotting all of the cells on these two characteristics, coloring the normal cells blue, and the cancerous red:

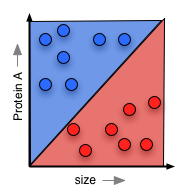

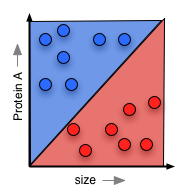

Now, if you're doing normal scientific induction, you'll look at this training data and try to posit a simple rule that will explain the data, and help you understand nature's "hidden rule" that makes some cells cancerous and others not. In classical statistics, this means you come up with a function that will "paint" part of the surface red, and part blue. This paint forms your prediction about any cell that lands in each region:

Vapnik helped found the field of

computational learning theory, in which one takes a slightly different approach. Rather than trying to guess nature's "hidden rule", you worry solely about minimizing the error your function will have when you test it against more liver cells. The surface-painting you come up with might not be parsimonious or a sensible guess about what nature is doing, but if it is a successful predictor, that's fine.

Now comes the upheaval that is transductive reasoning. Vapnik has established mathematically that you pay a certain price in the accuracy of your predictions by generalizing to pain the entire surface either red or blue. So his idea is this: rather than first doing induction to posit a general rule, then making predictions about new liver cells as you see them, you simply

transduce to make a prediction about each new cell as you see it, based on everything you've seen before. You don't get a simple rule that you can explain or write down -- all you get is a prediction each time. Vapnik has demonstrated that transduction will

always perform better than induction on a given problem.

So this leaves us with this abbreviated scientific method, in which we:

- Make a number of observations

- Use transduction to make predictions about new phenomena as we encounter them.

At least in particular problems in applied science, this really could be an upheaval. Who cares about having tidy theories and approximations of nature's mysterious inner ways if we can always have the better predictor? As a general approach to natural science, however, it's problematic. We induce models that measure the importance of Protein A not just so that we can make great predictions of whether a cell is cancerous. We also want to know whether we should investigate Protein A more deeply, learn about its structure and function, or invent drugs to mimic or inhibit it. Transduction doesn't help us make these decisions, and so we will always need some inductive reasoning along with our transductive predicting.

Thus far, the potential impact of transduction has only begun to make an impression on the philosophical community. I haven't found any discussion of it in the philosophy of science, but that could be because I don't understand the current problems and arguments in that field.

Gilbert Harman, a former professor of mine, is making an intriguing application of transduction to moral reasoning in a paper to be published later in 2005 (

RTF,

HTML). Essentially, Harman asks whether, if transduction can offer superior classification, we shouldn't attempt to use transduction to "classify" moral actions into "should do" and "shouldn't do." We would sacrifice the formation of inducing general moral principles which we could elaborate and trasmit, but we would (presumably) gain "better" moral decisions.

Is it worth giving up comprehensible theories for better predictions? Will we see transductive inference gain a foothold in economics, finance, the social sciences? It's one to watch.

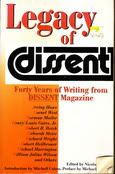

Legacy of Dissent

ed. by Nicolaus Mills

Dissent Magazine is my favorite contemporary political journal (admittedly, of like three that I ever read). It's avowedly left-wing, so it doesn't try to be all things to all people (like some). Yet unlike many left-wing magazines, it doesn't waste your time with choir-preaching conservative-bashing that serves merely to make you feel righteous, rather than advance a discussion (like a few magazines I can think of). Rather, it devotes its energy to liberal self-critique, challenging of orthodoxies, and honest insight into what in the liberal agenda is both moral and practicable.

I was vaguely aware of Dissent's history as a noteworthy anti-Communist (but pro-democratic-socialism) voice in the post-WWII landscape, so I was excited to stumble onto this collection of essays spanning the history of the magazine.

Well, my overwhelming impression is: Socialist thinking was by and large a bunch of dreck, man. For an anti-Communist magazine, they spent a lot of time quoting Marx, debating what Marx really would have wanted, and cooking up their vision of what a just society would look like. Peering from the far side of the millenium, this stuff reads like so much hooey.

The cultural writing, on the other hand, retains immense social and historical interest, and there are some real gems here. Paul Goodman's "Growing Up Absurd", from 1960, charts the emergence of the Beats and a whole generation of "Independents", who are not outside of the economic system, yet do not properly belong to it:

Legacy of Dissent

ed. by Nicolaus Mills

Dissent Magazine is my favorite contemporary political journal (admittedly, of like three that I ever read). It's avowedly left-wing, so it doesn't try to be all things to all people (like some). Yet unlike many left-wing magazines, it doesn't waste your time with choir-preaching conservative-bashing that serves merely to make you feel righteous, rather than advance a discussion (like a few magazines I can think of). Rather, it devotes its energy to liberal self-critique, challenging of orthodoxies, and honest insight into what in the liberal agenda is both moral and practicable.

I was vaguely aware of Dissent's history as a noteworthy anti-Communist (but pro-democratic-socialism) voice in the post-WWII landscape, so I was excited to stumble onto this collection of essays spanning the history of the magazine.

Well, my overwhelming impression is: Socialist thinking was by and large a bunch of dreck, man. For an anti-Communist magazine, they spent a lot of time quoting Marx, debating what Marx really would have wanted, and cooking up their vision of what a just society would look like. Peering from the far side of the millenium, this stuff reads like so much hooey.

The cultural writing, on the other hand, retains immense social and historical interest, and there are some real gems here. Paul Goodman's "Growing Up Absurd", from 1960, charts the emergence of the Beats and a whole generation of "Independents", who are not outside of the economic system, yet do not properly belong to it:

Now, if you're doing normal scientific induction, you'll look at this training data and try to posit a simple rule that will explain the data, and help you understand nature's "hidden rule" that makes some cells cancerous and others not. In classical statistics, this means you come up with a function that will "paint" part of the surface red, and part blue. This paint forms your prediction about any cell that lands in each region:

Now, if you're doing normal scientific induction, you'll look at this training data and try to posit a simple rule that will explain the data, and help you understand nature's "hidden rule" that makes some cells cancerous and others not. In classical statistics, this means you come up with a function that will "paint" part of the surface red, and part blue. This paint forms your prediction about any cell that lands in each region:

Vapnik helped found the field of

Vapnik helped found the field of