The idea is that I record a few favorite passages and any take-home thoughts I have from books as I read them. These aren't summaries or book reviews, so their utility may be limited for the dear readers.

This one is catch-up from a couple of weeks ago:

Fighting Years: Black Resistance and the Struggle for a New South Africa by Steven Mufson

Fighting Years: Black Resistance and the Struggle for a New South Africa by Steven Mufson

Written in 1989, after the mid-80's revival of the liberation movement in South Africa, but before the freeing of Mandela and the end of apartheid. Two rather simple lessons stand out for me:

1. Counterinsurgencies actually can work, and liberations can fail.

Watching

The Battle of Algiers, it's easy to draw the conclusion that

when you're fighting for liberation and self-determination, victory is a historical inevitability, and counterinsurgency only cuts heads from an indomitable hydra. In the modern context this may be true, viewed from a sufficient distance. But there were determined, popular, and well-organized black liberation movements that had the entire nation of South Africa ablaze in 1960, in 1979, and 1985. And each time, with ruthless persecution of the leaders, squelching of the free press, and concessions to the material and social well-being of the underclass, the government pretty well stamped each movement out. So damn, these things are hard, it turns out. I suppose a Palestinian or Tibetan could remind me of that.

2. The question of the use of violence in a liberation movement is not a simple one. I have always maintained, along with the rest of my 8th grade social studies class, that Gandhi and Martin Luther King were

good men. No controversy there. The question is, is their path truly the only just one?

There's a moment in the book in which a crowd seizes a suspected police informer. They begin to force a tire around his shoulders, in preparation for

necklacing. Bishop Desmond Tutu jumped into the crowd, cradled the informer in his arms, and told the mob they would have to kill him first.

A few days later, speaking to an extremely skeptical crowd, he tried to explain his actions. He raised his arms in a Christ-like pose, and said:

I understand when people are angry or hurt and want to take it out on those we think are collaborators. But I abhor all forms of violence. I want to condemn in the strongest terms what happened in Duduza [an internationally televised necklacing]. Many of our supporters around the world said then "Oh, oh. If they do those things maybe they are not ready for freedom." Let us demonstrate the discipline of people who know that they are ready for freedom. At the end of the day, we must be able to walk with our heads high!

It's a great speech, and the practical and moral lesson is clear, but the crowd was unimpressed. Years of nonviolent efforts had resulted in nothing but exile or death for the leaders. George Orwell once wrote a short essay (forget the name? Ah.

Reflection on Gandhi) in which he alleged that a non-violent campaign like Gandhi's, intended to appeal to the conscience of the oppressor, would simply fail in a country where dissenters disappeared in the middle of the night. South Africa was such a country, and the conscience of the whites was simply not stirred.

Not until whites faced civil unrest, difficulty traveling through the countryside, and rebellious youth throwing stones in downtowns of "white" cities did they take notice. So perhaps, just perhaps, there is room in my moral universe for violent acts, at least directed against property, and against uniformed enforcers of the oppression.

Alright, hafta cut this short. cheers.

Dance, Dance, Dance by Haruki Murakami

This is the first Murakami novel I've read, having stalled out on Norwegian Wood a few years ago. It's a sheer delight, a deeply weird story of an aimless 34-year old freelance writer, his aquaintance from middle school (now a movie star), three call girls, an intensely beautiful teenage psychic, a one-armed American poet who spends his days fixing sandwiches, a failed writer named Hakari Makimuri, and the Sheep Man who inhabits a separate reality.

The novel is what I understand to be a Murakami trope: disaffected thirtysomething, unsure what he's accomplishing in his life, alienated by his meaningless job "shoveling cultural snow", and unable to forge true connections to the people around him. He trudges through, distracting himself as best as possible, while wondering if and when things will change. There are a few hopeful sparks amidst a fundamentally disheartening series of events, and in the end it's only vivid personalities that we have to hold onto.

With such an oddball cast, there's much not to relate to, but I identify with this brief passage, with the protagonist on a quasi-date with the teenage psychic:

Dance, Dance, Dance by Haruki Murakami

This is the first Murakami novel I've read, having stalled out on Norwegian Wood a few years ago. It's a sheer delight, a deeply weird story of an aimless 34-year old freelance writer, his aquaintance from middle school (now a movie star), three call girls, an intensely beautiful teenage psychic, a one-armed American poet who spends his days fixing sandwiches, a failed writer named Hakari Makimuri, and the Sheep Man who inhabits a separate reality.

The novel is what I understand to be a Murakami trope: disaffected thirtysomething, unsure what he's accomplishing in his life, alienated by his meaningless job "shoveling cultural snow", and unable to forge true connections to the people around him. He trudges through, distracting himself as best as possible, while wondering if and when things will change. There are a few hopeful sparks amidst a fundamentally disheartening series of events, and in the end it's only vivid personalities that we have to hold onto.

With such an oddball cast, there's much not to relate to, but I identify with this brief passage, with the protagonist on a quasi-date with the teenage psychic:

The Biblical Flood by Davis A. Young

The Biblical Flood by Davis A. Young Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino

Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino The Nazi Seizure of Power by William Sheridan Allen

The Nazi Seizure of Power by William Sheridan Allen Fighting Years: Black Resistance and the Struggle for a New South Africa by Steven Mufson

Fighting Years: Black Resistance and the Struggle for a New South Africa by Steven Mufson

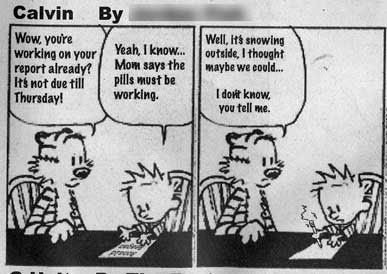

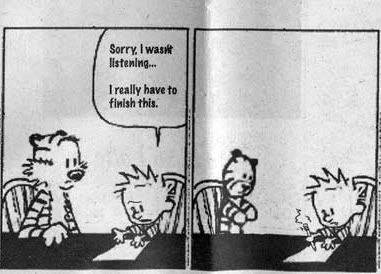

Sniff. Growing up is hard.

(via

Sniff. Growing up is hard.

(via